"Django Unchained" opens with a pitiful sight: our hero Django (Jamie Foxx), with haunted eyes and his feet in shackles, is marched across a barren landscape by a pair of brutal slave traders. The desperation and cruelty of his plight is laid out in bloody lash marks across his bare back. In typical Quentin Tarantino fashion, these images are juxtaposed by the theme song, a melodramatic ballad that sounds almost like a parody of western theme songs:

Django!

Django, have you always been alone?

Django!

Django, have you never loved again?

As he has so often proved during his career, Tarantino is the master of matching an incongruous needle-drop with harrowing images (just think "Stuck in the Middle With You" in "Reservoir Dogs") to the point where the tune feels like it could have been written specially for the movie. The lyrics here suit what we soon find out about Django, forced into solitude by his dismal status as an enslaved person, on a mission to find his wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington). She is separately held in servitude to the evil plantation owner Calvin J. Candie, played with meme-inspiring relish by Leonardo DiCaprio.

Since this is a Tarantino film, the title song was lifted with great effect from another movie. "Django Unchained" is the middle instalment of the magpie auteur's revisionist history trilogy, between taking revenge on the Nazis in "Inglourious Basterds" and giving the murdered actress Sharon Tate a happy ending in "Once Upon a Time in Hollywood." This time, he takes it upon himself to deliver a bit of rough justice to the slave owners of the 19th century, drawing inspiration from the spaghetti westerns of the '60s. One in particular stands out, thanks to its name and this title tune: Sergio Corbucci's wild and bloody "Django."

So What Happens In Django Again?

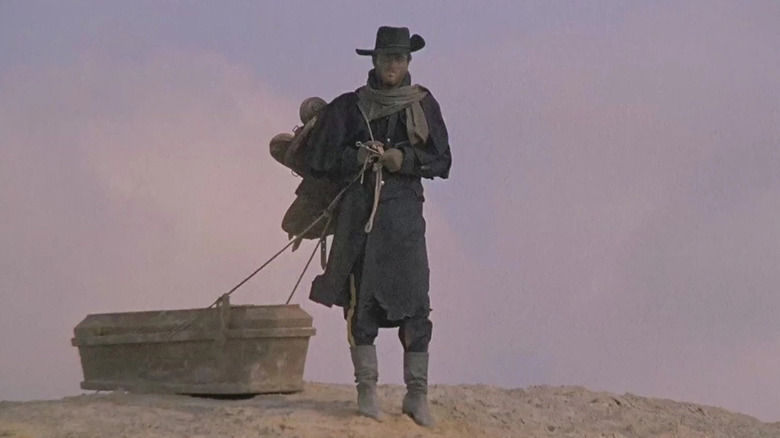

We're used to the old western trope of a stranger riding into town and taking out the bad guys before riding off into the sunset again, but Corbucci's "Django" opens with a surreal image that inverts it completely. Instead of opting for the mobility of a horse, our protagonist Django (Franco Nero) is on foot, in a tattered Union uniform, dragging a coffin through the mud. The wooden box contains his main method of mowing down his enemies, and the burden it presents is a striking metaphor. It is his albatross, and it lends the character a mythic quality.

He spots a gang of Mexican bandits torturing a prostitute named Maria (Loredana Nusciak). He doesn't deem this worthy of intervention, but then some ex-Confederate dirtbags arrive and shoot the bandits dead, only to prepare a crucifix to burn the woman alive. Django finally rescues her with a little gunplay worthy of Clint Eastwood's Man With No Name.

Django and Maria continue to a muddy ghost town where our laconic protagonist has unfinished business, visiting the grave of an old girlfriend who was murdered by Major Jackson (Eduardo Fajardo), head of the white supremacist gang who enjoy shooting Mexican peasants for sport. The town is torn between Jackson's crew and a band of Mexican revolutionaries led by General Hugo Rodriguez (Jose Bodalo), who are almost as bad.

Django goes to war with both sides, and the plot turns into a frankly baffling series of double-crosses and bloody confrontations. There is a standout moment when Django busts out the contents of his coffin against a whole army of Jackson's goons, and a wild excursion as he helps Rodriguez pull off a daring bullion heist. It could all be ripped straight out of the pages of a pulpy western comic book.

The Original Django Controversy

The cartoonish levels of violence in "Django" caused controversy when it was released, regarded as one of the most violent movies ever made at that point. It received an 18 certificate in its native Italy and struggled to find a distributor in the US until the early '70s, presumably helped along by the carnage of "The Wild Bunch." It was banned outright in Sweden, and the notoriously fusty censors in Britain refused it a certificate due to the "excessive and nauseating violence." It didn't receive a certificate in the UK until 1993, when a new examiner took a different view (via BBFC):

Although two decades ago the feature may have seemed mindless violence, in the age of "Terminator 2" and Arnold Schwarzenegger, the feature has an almost naive and innocent quality to it. The mass shoot-outs where one bullet can descend a score of cowboys, what is remarkable is the absence of impact shots, blood spurts, and splatter. One could say the feature is almost entirely bloodless.

Well ... maybe. Artistically, there is enough about Corbucci's vision to separate it from the scores of other violent movies that fell foul of the British censors, especially during the era of the video nasty, but I think the guy was missing the tone entirely. Sure, for the amount of people who die in the movie there is relatively little gore, but the film's sheer gung-ho nature makes it feel even more violent than it actually is, even over half a century later. There is an irreverent glee to the bloodshed, which may explain why Tarantino, himself never shy of depicting a bit of OTT violence, loved it so much in the first place.

Despite — or perhaps thanks to — its violent reputation, "Django" was a big hit and spawned over thirty unofficial sequels. The stoic, blue-eyed Franco Nero only starred in one more official Django sequel, "Django Strikes Again" in 1987.

Django Unchained Wasn't The Only Tarantino Movie That Borrowed From Django

Compared to some of his other movies, Tarantino's borrowing from "Django" for "Django Unchained" is quite light. There is the title and the theme song, a sort-of torch passing cameo from Franco Nero, and parallels found in the whipping scene and the comedic moment when the KKK can't get their pillowcase masks right. Otherwise, the connection between the movies is more thematic, with the ex-Union soldier taking the racist ex-Confederate bad guys down. As Tarantino makes clear in the recent Netflix documentary "Django & Django," his film is more a celebration of Corbucci's work as a whole, rather than just the one film.

This is reflected in the other Corbucci homages in "Django Unchained." Firstly, Django's savior and partner Dr. King Schultz (Christopher Waltz) is a German bounty hunter, echoing Klaus Kinski's character in "The Great Silence," which is often regarded as Corbucci's best film. That film's wintry backdrop, set after a great blizzard, is referenced in the montage where Schultz tutors Django in the ways of bounty hunting in a similarly snowy environment. Another little nod comes in the scene when the pair visit a saloon named Minnesota Clay, which is also the title of an earlier Corbucci movie.

"Django Unchained" may not be the only Tarantino movie that quotes "Django." While some sources cite the torture scene in "The Big Combo" as the ear-slicing scene in "Reservoir Dogs," that is very much to do with how the guy is tied to a chair and writhes around as he is abused. For the actual act of cutting itself, we have a very similar moment here when Rodriguez slices off a poor victim's ear and feeds it to him, before shooting him in the back. Knowing how Tarantino loves mashing his favorite scenes together, it was probably a bit of both.

Sergio Corbucci, Making Leone Look Like A Pacifist

According to All Outta Bubblegum, a site that catalogues the body count of various violent movies, "Django" clocks in with 180 kills. Our hero accounts for over half that total. That figure comes as some surprise, because it's so gratuitous that it feels like a lot more. On top of that, we have four scenes that feel especially sadistic: Maria's torture and near-burning; the ear-cutting scene; Jackson and his cronies gunning down some scared Mexican peasants; and, Rodriguez's men mangling Django's hands to a bloody pulp. If Sergio Leone's revered "Dollars Trilogy" upped the stakes for violence in westerns, "Django" goes all-in, combining elements of Leone's films and heightening the spaghetti western to an almost surreal plane. Beyond the flying bullets and bodies, you have bizarre moments like Django breaking into a house through a chimney to steal some gold while still lugging his coffin, and the spooky beauty of the final showdown in a cemetery.

Some critics felt that "Django" was a substandard ripoff of Leone's films, but what really separates it is the nihilistic tone. A lot of people die in Leone's movies and there are some very cruel moments — not much beats the scene in "For a Few Dollars More'" when the villain has a snitch's wife and kid shot before offering him a rigged opportunity to gain revenge — but they still have their own clear moral compass. By contrast, the ethics of Corbucci's movies are hellish. As Tarantino, a big fan of the director, wrote (via New York Times):

"Sam Peckinpah had his own West; so did Sergio Leone. Sergio Corbucci did, too — but his West was the most violent, surreal and pitiless landscape of any director in the history of the genre. His characters roam a brutal, sadistic West ... Corbucci's heroes can't really be called heroes. In another director's western, they would be the bad guys."

Well, I can't really argue with that. Django is a stone-cold killer torn between the very bad guys and the even worse bad guys, and makes vulture fodder of them all.

Read this next: /Film's Top 10 Movies Of 2021

The post The Controversial Spaghetti Western That Inspired Tarantino's Django Unchained appeared first on /Film.

0 Commentaires