Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia's feature-length debut "The Platform" (released as "The Hole" in its native Spain) debuted in March of 2020 on Netflix. It quickly became one of the streaming platform's most successful original movies with over 56 million views.

The film tells the story of residents imprisoned in a tower-like building, fed by a platform which — after being laden with food at the top — descends slowly through the structure. Those at the higher floors eat heartily, with subsequent lower floors only getting the leftovers from the level previous. It's as heavy-handed a social allegory as you're likely to find, but the central message is a powerful and eternally topical one, namely that there are enough resources for everybody but little incentive for those on the top to share with those below.

The structure in "The Platform" is a metaphor for social inequality as much as it is a reminder of the Vladimir Lenin quote, "Every society is three meals away from chaos." Desperate people will go to desperate measures, and it proves to be surprisingly easy to reject social norms and sink into depravity or barbarism when your life depends on it. If you were particularly fond of the social metaphor in "The Platform," here are a number of other movies that may pique your interest.

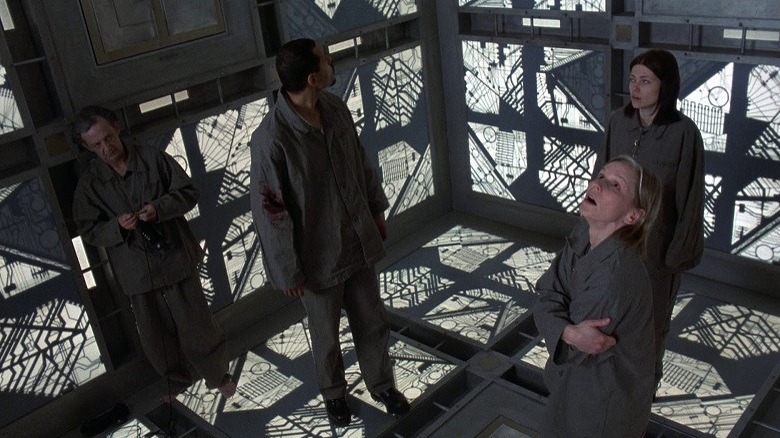

Cube (1997)

Lacking any of the political parallels of "The Platform," though certainly sharing a common theme of imprisonment and fighting for survival, 1997's "Cube" is a textbook example of how to do thought-provoking science fiction on a meager budget with a small cast.

A group of disparate strangers wake up in a maze of cuboid rooms of different colors, none of whom are able to recall how they arrived here. They soon learn that some of the rooms contain lethal traps, and only by working together to combine their requisite strengths do the individuals stand any chance of escaping this deadly labyrinth.

Much as with "The Platform," the combination of desperation and the inevitable clash of personalities means that the individuals in question pose as much of a threat to each other as the structure itself. However, it is the convincing cast and various mysteries in play behind "Cube" ("Why are they there?" "What is the purpose of the prison?") that propel the energetic plot forward. From the memorable opening scene onwards, the pace barely slows. A mostly unnecessary sequel and an entertaining prequel followed (revealing many of the Cube's secrets), and a Japanese remake emerged in 2021.

Joker (2019)

"The Platform" shows us that humankind, for all our bold claims of empathy and refinement, will lean towards selfishness in truly desperate situations when the veneer of civilization breaks.

In the Gotham of 2019's "Joker," society is falling. Super rats feast off the growing heaps of garbage dotting the streets (a none-too-subtle metaphor) whilst the wealthy 1% prosper, ignoring or rejecting the growing underclasses beneath them. Even Thomas Wayne — father of Bruce and known philanthropist in Batman canon — is guilty of this, running for Mayor but with seemingly little genuine concern for the citizens.

Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), failing at both clowndom and life, ultimately comes to represent what happens when an individual no longer tries to hide the evil within, choosing instead to embrace it. It's a similar nihilistic view to that of 1976's "Taxi Driver," with the casting of Robert De Niro in "Joker" only reinforcing that. This is one of the bleakest yet most powerful movies on this list.

A far from traditional origin tale considering the character's comic history, "Joker" feels far removed from the DC Universe, something that only works to the movie's credit. Joaquin Phoenix's portrayal of the Clown Prince of Crime is truly standout, which is no mean feat considering the other actors who have donned the white face paint.

Parasite (2019)

The phenomenal success of Bong Joon-ho's 2019 movie "Parasite" cannot be understated, nor its landmark importance as the first South Korean nominee as well as the first foreign language film to receive a best picture Oscar from The Academy.

Reaffirming that the themes of class and inequality are universal worldwide, "Parasite" follows the Kim family, impoverished and down on their luck, and their attempts to gradually infiltrate the lives of the affluent Park family. Like the titular organism of the title, the Kim family begin to slowly take over the Park's lives, as more of the Kim family gain employment within the household through lying and subterfuge.

The seemingly literal title "Parasite" also proves to have a double meaning. The Parks themselves are gullible fools, barely able to perform the simplest of tasks without the Kims assistance, so who is the real parasite? With some great performances and genuine rug-pulls, "Parasite" entertains from start to finish, with an ending that you'll never see coming.

They Live (1988)

With the subtlety of one of "Rowdy" Roddy Piper's punches from this movie's lengthy fight scene, John Carpenter's 1988 movie repeatedly drives home a political allegory. When blue-collar worker Nada (portrayed by wrestler Piper) finds some discarded sunglasses and puts them on, the true nature of the world is revealed to him.

Like Neo from "The Matrix" waking in a vat and finding out he's nothing but a fancy rechargeable battery, Nada suddenly sees the world for what it really is: A place where the underclasses are being kept in a state of torpor by a dominant alien race, subliminally encouraged to keep the wheels of capitalism relentlessly turning until the day they die. It's also worse than it first appears, as humanity is complicit in the betrayal of its own species, the upper echelons of society extremely happy to skim from the top and keep the status quo exactly as it is.

Despite the sci-fi trappings, it's a powerful message, and as relevant now as it was in the '80s. Piper, here playing an everyman (even his character's name "Nada" means "nothing"), is convincing throughout and has some of the most quotable lines in cinema history.

Get Out (2017)

Allegories of social hierarchy are common in horror and speculative fiction, with Brian Yuzna's 1989 "Society" to name just one, but rarely are they as elegant or topical as in Jordan Peele's superlative "Get Out."

Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) is invited to his girlfriend's parents for a weekend break, nervous about her family's potential reaction to their interracial relationship. This is far from an update of 1967's "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" (starring the late lamented Sidney Poitier) though. Chris's initial fears are defused as they seem overly — even uncomfortably — accommodating, but he learns of something far more sinister brimming under their cozy liberal facade.

Peele's inheritance of the "Twilight Zone" legacy feels apt after this, as "Get Out" plays like an episode of the classic series expanded to feature-length. What may initially seem to be a straight satire on racism turns out to hold far greater depth, with recurring themes (the silver spoon and deer motifs in particular) rewarding multiple viewings. It's as much science fiction as psychological drama, but even a far-fetched ultimate reveal that threatens to derail the plot doesn't ultimately detract from the film's confidence and power.

District 9 (2009)

"District 9" wasn't writer/director Neill Blomkamp's first stab at satirizing Apartheid — that was 2006's "Alive in Joburg," the short film that inspired it — but it hit cinemas with such impact that Blomkamp has struggled to match its success.

Three decades after alien refugees landed on Earth, they're now housed in shanty towns in South Africa. A mega-corporation is responsible for their welfare, yet is more concerned about obtaining alien technology than providing the alien visitors ("Prawns," as they're cruelly nicknamed due to their amphibian appearance) with adequate food and shelter. When one of the corporation's own agents is exposed to alien technology that begins to rewrite his DNA, he's forced to seek shelter in District 9, the most notorious of all of the ghettos.

"District 9" takes the term "illegal aliens" to its logical conclusion, showing that we treat our extraterrestrial refugees just as badly as we treat the terrestrial ones. It's an allegory for human prejudices springing from fear of "the other," as well as a timely reminder that these different-looking strangers are not that dissimilar to us. The final act moves away from the message in favor of more traditional sci-fi with robots and lasers, but "District 9" still stands up as Blomkamp's strongest work.

Trainspotting (1996)

Few films have ever captured the U.K. zeitgeist as effectively as Danny Boyle's "Trainspotting," based on Irvine Welsh's debut novel of the same name. One of those movies where the soundtrack is as much a character as any actor, it took full advantage of the burgeoning musical movement labeled "Britpop," opening with phenomenal popularity and critical acclaim.

Like Boyle's "Shallow Grave" before it, the plot basically involves our lead characters (predominantly Ewan McGregor's heroin addict Mark Renton) trying to escape the squalor and mundanity of their daily existence. Nearly two decades of Conservative government rule had created a huge wealth disparity, with the "Trainspotting" setting of Scotland hit particularly hard. With unemployment so high as to make obtaining a job next to impossible, the only way to escape for many was through hard drugs. When money is tight, the cocktail of drugs can prove lethal for many.

Life is the prison in "Trainspotting," where the bleak view is that the only escape for some is through oblivion or overdose. It's a wry and provocative view of friendship, poverty, and thwarted ambition.

In Time (2011)

Taking the idiom "buying time" at its most literal, Andrew Niccol's "In Time" posits a dystopian future where mortality has been conquered by genetic engineering. However, this luxury comes at a literal cost: People stop aging at 25, but additional life costs more, resulting in the wealthiest in society becoming virtually immortal. "Time is money" has never been so apt for factory worker Will (Justin Timberlake), who — upon being gifted with a century on his life-clock by a man he saves — finds himself on the run with a hostage, accused of murder.

"In Time" shares more than a little DNA with Andrew Niccol's 1997 debut "Gattaca," both being effective science fiction thrillers about discrimination and injustice set in a recognizable near-future. For a movie with a central premise of time as currency, it adequately conveys lofty ideas and effective set pieces in its running time, and Timberlake's Will (and his hostage Sylvia, played by Amanda Seyfried) make for a very watchable Bonnie and Clyde-type duo. Comparisons to 1976's "Logan's Run," which has a similar premise of people voluntarily euthanizing themselves at the age of 30, are unavoidable, but "In Time" deserves at least 109-minutes of your time.

Snowpiercer (2013)

An ecological disaster has caused a second ice age, and the survivors share a never-ending train named Snowpiercer that hurtles across the lethally-cold terrain of an uninhabitable Earth. The wealthy live at the front in decadence and luxury, while the poor huddle together in the rear cars under armed guard. Chris Evans plays Curtis Everett, a caboose dweller who — upon realizing the guards ran out of bullets long ago — starts a revolution, encouraging his followers to storm towards the front of the train.

Based on the French graphic novel "Le Transperceneige," this is writer/director Bong Joon-ho's more fantastical predecessor to "Parasite," a metaphor for society set on train tracks. It's the structure of "The Platform" laid onto its side, not to mention an action movie with brains. You'll find it easy to ignore the convoluted central premise when the plot relentlessly plows forward with the horsepower of Snowpiercer itself. Topped off by a frankly stellar international cast (including Song Kang-ho, Tilda Swinton, Jamie Bell, Octavia Spencer, John Hurt, and Ed Harris), this is certainly one train you don't want to miss. All aboard!

Battle Royale (2000)

Fans of the bloodthirsty rivalries of Netflix's recent "Squid Game" will appreciate this Japanese horror thriller from 2000. As a somewhat extreme measure to combat juvenile delinquency, the totalitarian government kidnaps 42 14-year-olds and leaves them on a deserted island, each fitted with an explosive collar that will detonate if they break the rules. Forced to scavenge for supplies and weapons, they each have one objective: To be the last student standing and thus be allowed to leave the island. It's "Lord of the Flies" with semi-automatic weaponry.

As with "The Platform," the plot is driven not just through extreme violence (and the somewhat disturbing concept of 14-year-olds trying to slaughter each other), but seeing the varying armistices and rivalries emerge between the disparate group of prisoners. Ultimately nobody is to be trusted, but as the numbers begin to whittle down the possibilities emerge to turn the tables on their captors. It's a premise borrowed by "The Hunger Games," which was considerably more bloodless. A poor sequel titled "Battle Royale II: Requiem" emerged three years later, relievedly subverting the formula of the first movie but with nowhere near the same entertainment value.

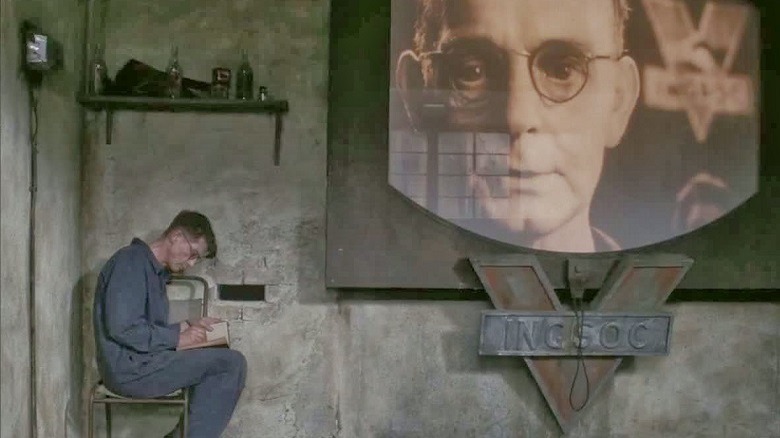

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984)

The term "Orwellian" has fallen into overuse, but you can be fairly safe saying it about author George Orwell's own works. The film version of his 1949 novel "1984" (released in the only year it could ever have been released) follows Winston Smith (John Hurt), a civil servant working for a despotic government in a dystopian alternate reality. Only his love for Julia (Suzanna Hamilton) brings him any respite from this intolerable life, but their relationship is forbidden ... and nothing escapes the gaze of the dictatorial Big Brother.

It's a story that has pervaded so many elements of modern culture, being responsible for the terms "Big Brother" and "Thought Police," that it's difficult to view "Nineteen Eighty-Four" in a properly critical light. The book is one of the most famous pieces of literature of all time, and the film — in no small part thanks to a superb central performance by Hurt — does the source material more than justice. His anguish and breakdown are tangible, as the system existed long before Winston Smith, and it will continue long after. Like "The Platform" as it descends to the lower levels, all cinematic dystopias are just feeding off the scraps from the bleak feast that is George Orwell's "1984."

High-Rise (2015)

Based on the 1975 novel by English writer J. G. Ballard (no stranger to a good dystopia, including his novel "The Atrocity Exhibition"), Ben Wheatley's 2015 film is set in an opulent 40-story high-rise apartment block on the outskirts of London. With the poorer housed nearer the ground, the more affluent live towards the top with all the amenities including cinemas, offices, shops, and gyms. This particular high-rise is designed so its inhabitants should never have to leave.

Ultimately, though, this bold social experiment is doomed to failure. Isolated from the outside world, the disparate groups of inhabitants begin waging class warfare on each other, and one individual from the lower floors named Laing (Tom Hiddleston) begins his fight for supremacy.

The Mega-Blocks from "Dredd" (2012) are clearly influenced by Ballard's legacy, and the equivalent of Laing's literal fight for ascendancy can be seen in both that and "The Raid." "High-Rise" is an excellent adaptation of a work often considered unfilmable, adequately conveying the core elements of the building being a microcosm of society, with the oppressed fighting back against a group that literally towers over them.

Circle (2015)

With a high concept to rival "Cube," "Circle" opens with 50 strangers standing in positions around the circumference of two concentric circles, all oblivious to how they ended up there. Anybody who moves out of their allotted position is summarily executed by an unseen foe. Every two minutes, an individual from the group — seemingly chosen at random — is also slaughtered.

That alone wouldn't make for a particularly entertaining premise. However, the individuals soon learn that by voting they can influence who gets chosen for execution, and the film's ability to captivate a cinema audience for what is effectively watching people argue passionately with one another is fascinating and at no stage feels laborious.

We are, of course, witnessing a grand psychological experiment. Despite the large cast, characters' personalities and true natures emerge, and in acts of self-survival seek to exploit the prejudices of others to their own ends. Desperation increases to the fever pitch of the final act, and the denouement is as rewarding as it is cruel.

The Killing Of A Sacred Deer (2017)

"The Platform" ultimately shows us what happens when a monkey wrench is thrown into the works of a closed system. Goreng, the movie's imprisoned protagonist, is a disruptive influence that seeks to break a system that could be argued was working as intended.

Yorgos Lanthimos' "The Killing of a Sacred Deer" follows Steven (Colin Farrell), a wealthy and successful heart surgeon with a loving family. Like Banquo's ghost in Macbeth, a young man named Martin (Barry Keoghan, appearing with Farrell again in "The Batman") enters their life, gradually and deliberately throwing it into turmoil.

Inspired by the 2500-year-old Euripides play "Iphigenia in Aulis," it's a story of betrayal and ultimate sacrifice. Martin is like a vengeful God, throwing a perfectly orderly and structured family unit into disarray, with a dark motive that propels the movie into its poignant final act. It's an unnerving watch, with much of the dialogue delivery feeling deliberately stilted and artificial. It's part horror, part psychological thriller, and is thoroughly gripping.

Read this next: The 20 Best Dystopian Movies Of All Time

The post Movies Like The Platform You Definitely Need to See appeared first on /Film.

0 Commentaires