"There is no such thing as an action movie," says Steven E. de Souza, writer of more than one film venerated below, "'Action movie' is a term that was invented in the '80s." He's not wrong. Before the MTV age, action was diversified. Swashbucklers. Westerns. War epics. Crime thrillers. Fists of fury. All the way back to Buster Keaton, audiences thrilled at feats of derring-do, but action was just another tool in filmmakers' boxes.

1982's "First Blood," the cinematic debut of John Rambo, contains only a single kill. "Rambo III," released just six years later, boasts a body count of 132, averaging about one-and-a-half murders per minute. At the time, the "Guinness Book of World Records" deemed it not only the most violent movie ever made, but also the most expensive at $69 million. $16 million of that went to Sylvester Stallone's paycheck, granting him further Guinness bragging rights as the highest-paid actor of all time.

The '80s belonged to action. Pectorals rippling with heavy recoil. Entire neighborhoods disintegrating in pyrotechnic displays. No end too grisly for a one-line eulogy. The decade produced some of the greatest action films ever seen, but the following 16 represent the very best of their iconic era.

Above The Law

In the decade's twilight, as muscle-bound supermen lost ground to special effects, two unlikely challengers entered the ring. They were Ferraris, not Hummers, making up for their standard humanoid proportions with bone-breaking speed. While Jean-Claude Van Damme wouldn't find his best showcase until the '90s, the case could be made that Steven Seagal never bettered his debut.

Seagal, an aikido expert who claims to have a past with the CIA, plays Nico Toscani, an aikido expert who has a past with the CIA. It's no stretch -- note Segal's "Story By" credit -- but here, the man has something to prove. Uber-agent Michael Ovitz believed he could make anybody a star, even his (alleged) martial arts instructor. So, as much as he ever would, Seagal tried.

Director Andrew Davis, fresh from wringing a performance out of fellow action hero Chuck Norris in "Code of Silence," presents Seagal as the punching man's Dirty Harry. He talks just as softly, but forgoes the .44-caliber stick. All Nico needs are his hands, held approximately steering wheel-width apart, and something he can flip the next scumbag into. The moves are still novel and the speed still impressive, but the biggest thrill is Seagal himself. When he monologues an old friend to pieces about the Agency's unchecked evil, it plays like a bounced check; he could've been a contender, or at least not Steven Seagal.

Octopussy

The James Bond franchise has been around long enough to double as a pop culture barometer, always a few years behind. Blaxploitation begat "Live and Let Die." The kung-fu craze begat "The Man with the Golden Gun." "Star Wars" begat "Moonraker." "Raiders of the Lost Ark" begat "Octopussy."

Its title does it no favors. Roger Moore, then 55, wanted to retire after the previous film and only returned after James Brolin threatened to replace him. "For Your Eyes Only" is a better thriller. "The Living Daylights," better espionage. But "Octopussy" is a go-for-broke barnburner that marks the height of Bond's crowd-pleasing excess.

Moore's climactic clown disguise is not an insult, but a mission statement. Forget the nouveau riche blockbuster class -- the 007-ring circus had been touring for decades, and could still show them all a thing or two. Marvel as the spy with a painted tear on his cheek defuses a nuclear bomb. Thrill as he threads the needle of an airplane hangar in a one-man jet. Snicker through popcorn as he invades the enemy compound via alligator submarine. Not only can he swing through the jungle higher and faster than Harrison Ford's dusty archaeologist, but Bond yells like Tarzan as he does it. A serious Cold War story lurks among the gags, but there's enough of those to be found in the films ahead. "Octopussy" is all about old-fashioned pomp and circumstance -- even the nail-biting finale is just a gussied-up wing walker act.

Cobra

According to the writer, star, and alleged ghost director himself, the inspiration for "Cobra" was a simple question: "What if Bruce Springsteen had a gun?" Sylvester Stallone's answer is not only incorrect even by the wildest of imaginations, but actually approaches modern art in its wrongness.

This is '80s Americana reduced to its basest perversions and arranged in a poppy montage. Mirrored aviators. Room-temperature Coors. Chromed-out muscle cars that are unsafe at any speed. Ax-wielding maniacs. European supermodels no wider than a sniper rifle's crosshair. Unexpected robots. Marion "Cobra" Cobretti lives under a giant, neon Pepsi ad and carries a gun with an illustrated grip that can only be seen when holstered like surrogate genitalia.

Every decision can be justified by an even simpler question -- "Is it cool?" -- and Stallone never misses. Why does Cobretti cut the tip of his pizza off with scissors? Why do three open freezers fog out most of a grocery store? Why does the murderous cult meet solely to clang axes together over their heads?

After the one-two punch of "Rambo: First Blood Part II" and "Rocky IV," Stallone had reached his personal event horizon. What he made with that unimaginable power is absurdist, fascist, and honest to its leather-and-denim soul. But boy is it cool.

Lethal Weapon 2

"Action movies before then," recalled "Lethal Weapon" director Richard Donner, "[were] all generic characters and gratuitous violence." His awed then refers to Shane Black's script for the original film. This awe does not extend to the script Black co-wrote with novelist Warren Murphy for the sequel, preliminarily called "Play Dirty." Donner found it too dark, and Black quit. Without Black's corrosive wit, the franchise could only get sillier -- beware the Warner Bros. logo, now scored with a Looney Tunes taunt.

"Lethal Weapon 2" is an R-rated cartoon. Martin Riggs, a formerly broken soul mended just barely by his surrogate family, makes his entrance while gleefully destroying said family's station wagon. Roger Murtaugh, too old for this the last time, almost dies on a toilet. Joe Pesci plays Porky Pig. There's just enough darkness to leave a bruise, but not enough to rule out decapitations-by-surfboard or the quip that always follows.

"Lethal Weapon" is the better movie, but "Lethal Weapon 2" is the better action movie. Donner reduces the original's neo-noir nihilism to window dressing and spends his doubled budget totaling entire car dealerships. This is the buddy cop blockbuster supreme, sold on a tagline so cocky it didn't even try: "The Magic Is Back." And how.

Righting Wrongs

The legendary Three Dragons -- Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, and Yuen Biao -- are responsible for some of the greatest action films ever made, together and apart. Of the trio, compatriots since their days at the Peking Opera School, Biao remains the most obscure to western audiences. That's a tragedy, especially considering that he's the best mover of the bunch.

In "Righting Wrongs," Biao puts that agility to brutal use as a lawyer who moonlights as judge, jury, and executioner. Anyone expecting prop comedy and pratfalls is in for a rude awakening -- the wrongs here are very wrong. The villains incinerate children because their parents saw something they shouldn't have. The heroes kill with extreme prejudice and unflinching cruelty. They're all free radicals condemned to the same terminally corrupt system. In the complete absence of justice, blood makes do.

The simplest confrontations escalate at blinding, occasionally nightmarish speeds. An attempted hit-and-run in a parking garage turns into a lop-sided demolition derby with Biao at one point dropping between the fenders of two crashing cars. A routine arrest by eventual ally Cynthia Rothrock, among the most unsung of '80s action heroes, climaxes with a 30-foot diving tackle off a balcony. The final showdown defies all expectations of bodily capability and happily-ever-after. Seek only the original Hong Kong cut -- the rest pull the fiercest, final punch.

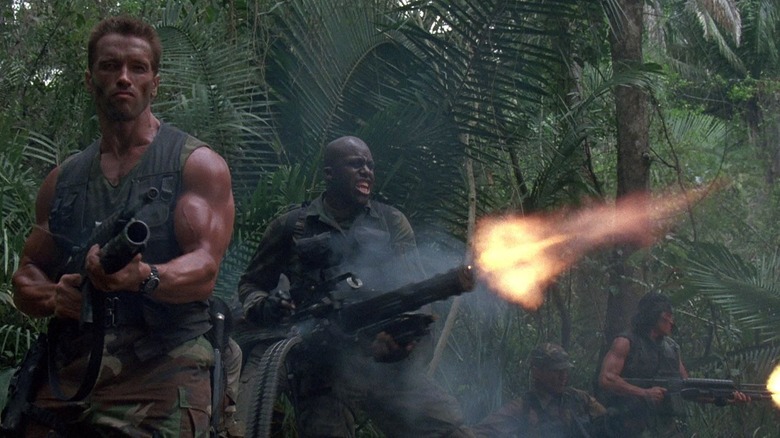

Predator

This is the most contentious inclusion on this list because, as much as it does scratch the genre's primal itches, "Predator" is more of a high-tech insult to greased-pec action cinema than a proud example.

The testosterone airs out early. The now-immortal bicep measuring contest. Jesse Ventura coining the phrase "sexual tyrannosaurus." Bill Duke dry shaving on a shuddering helicopter. To director John McTiernan's continued annoyance, the village assault even looks like second-unit business as usual. But then the one-liners disappear in the lush desolation and the supermen do something unthinkable: They panic.

Muscles are no match for lasers, cloaking devices, or similar special effects. One of the toughest ensembles ever collected on celluloid dies horribly, man by man, until all that's left is the least-killable action hero in history. Arnold Schwarzenegger meets his impossible match and gives his best performance of the decade. The horror bona fides of "Predator" may dilute its standing, but there's no more potent representation of '80s action than the buffest actors in the world unloading thousands of rounds into the empty jungle just to hear the reassuring sounds they make.

Runaway Train

No discussion of '80s action films would be complete without mentioning Cannon, the studio that Chucks Norris and Charles Bronson built. Schlock was its calling card and lifeblood. Lurid B-pictures made for peanuts and pre-sold into the black on home video rights kept the lights on. Today, its legacy glows in cheap neon with beloved junk like "Death Wish III" and "Enter the Ninja," but between those efforts, Cannon funded projects by renowned filmmakers who were no longer bankable in the blockbuster age.

"Runaway Train," the one-time pet project of Akira Kurosawa, splits the difference as an existential rumination on the same bitter, sometimes nihilistic resilience of the human spirit that also taught "Speed" everything it knows. Jailbirds Jon Voight and Eric Roberts make their escape aboard a locomotive headed across the Alaskan tundra. Almost immediately, the conductor dies, condemning the pair (and eventual trio) to a one-way trip sans brakes.

Russian director Andrei Konchalovsky boils the journey down to its rawest materials. Blistering wind. Severed fingers. Relentless momentum. Life and death. "Runaway Train" is the only action movie on this list -- and perhaps cinema as a whole — that not only ends with a quote from "Richard III," but earns it.

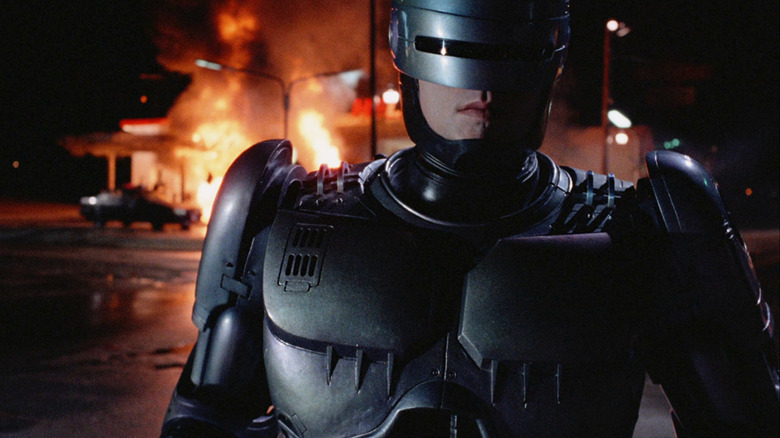

RoboCop

"RoboCop" was rejected by the MPAA eight times over its sloppy-joe gore. "The violence in the film is amplified because I thought it had to do with Jesus," defends director Paul Verhoeven. "RoboCop's an American Jesus."

Corporate interests bring officer Alex Murphy back from the dead. His first and, for a time, only surviving personality trait is cribbed from children's television. To paraphrase a later cinematic cop well-acquainted with bulky costumes, RoboCop was the toyetic hero Detroit needed. Only through self-discovery, stop-motion animation, and several thousand squibs does he become the hero it deserves.

The beauty of "RoboCop" lies in its straight-faced hyperbole. As much as it's a caustic commentary on hyper-violent American action movies, it, too, is a hyper-violent American action movie. Verhoeven never winks. Peter Weller studied Eisenstein's "Ivan the Terrible" to play his computerized half properly. Basil Poledouris' score doubles as an operatic mockery of the genuine article. It's a miraculous piece of work, and not just for the part where RoboCop walks on water. Then again, sometimes a sniper rifle that explodes sports cars is just a sniper rifle that explodes sports cars.

Rambo: First Blood Part II

In the future tradition of "Lethal Weapon 2," "First Blood Part II" is a lesser film than its forebearer. "First Blood" is a Frankenstein story, a sad and violent lesson about patriotic hubris. "Rambo: First Blood Part II," with the monster's name moved out in front, lets the creature loose to wreak the exact havoc he was broken and rebuilt for -- for the same country that broke and rebuilt him.

And what spectacular havoc it is. Rambo's defensive playbook gets thrown out with his most expensive gear; he's a slasher villain reunited with his campground of choice. Rambo doesn't just hide from patrols. He disguises himself as a mud bank and waits for the most dramatic moment to crack open an eye. Instead of ducking when a lone soldier opens fire on him, Rambo takes the time to string up an explosive arrow. The resulting viscera is documented with all the flair of a building implosion. Not that there's much time to waste on reflection -- an entire mountain blows up 25 seconds later.

For the first and last time with his runner-up franchise, Stallone attempts to circle a square. Rambo is both a state-conjured ghost and a GI Joe -- a Saturday morning cartoon starring Rambo premiered the following year. In just over an hour and a half, he single-handedly starts, ends, and wins a second Vietnam War. "First Blood Part II" is a Rosetta Stone of American pop culture during the Reagan years. It's not the best action film on this list, but it's arguably the most definitive.

The Killer

Once, while shooting "The Killer," director John Woo showed up on set and asked his producer to find 30 stunt performers and over 100 extras. When asked why he needed them, Woo said, "I don't know."

Woo made the film without a script or storyboards, a product of pure instinct. The result is the first Woo-brand bullet ballet, doves and all. It's cut from criminal myth. Chow Yun-fat is the kind of hitman who goes to church for the atmosphere. Danny Lee is the kind of cop who's either dedicated or deranged, depending on the commissioner's patience. The hitman wants to retire and make amends to the lounge singer he accidentally blinded. The cop can't believe a killer would care. Emotions are expressed through jabbed pistols and squeezed triggers. Friendship is earned in self-defense, back-to-back, against shared targets. The only forces of nature in Woo's Hong Kong are love and ammunition.

Though "Hard Boiled" has since taken the gold as the filmmaker's bullet-hell masterpiece, there's more to "The Killer" than its perfectly choreographed mayhem. This is opera as much as it is action. Woo's lifelong obsession with Jean-Pierre Melville finds its most powerful outlet here -- not only does he tap the same ice-cold vein, but he manages to find a bloody, beating heart at the end of it.

Aliens

James Cameron knows a great trick. He's pulled it off three times, with "Terminator 2: Judgment Day," "Aliens," and the script for "Rambo: First Blood Part II." How do you build a better sequel? Make it an action movie.

"Aliens" is the most daring of the bunch, not just for its harsher genre whiplash, but the professional context. Most of the British crew hadn't seen "The Terminator" yet, reducing fearless leader Cameron to the visionary director of "Piranha II: The Spawning." If the pressure or daily stalemate over tea time got to him, it doesn't show. If anything, that helps his case for stretching the world's worst shift into the world's worst career. Ellen Ripley just cannot catch a break. Sure, her coworkers brought guns this time, but the Xenomorph brought more Xenomorphs.

Dread is measured in ammo counts and blinking dots in the dark -- a sentry gun standoff reinstated in the Special Edition rhymes with the wasted rounds of "Predator." This is Cameron's Vietnam, the "Rambo" serial numbers slicked over with goo. Only Ripley knows how it ends. Her miserable tour of duty, which she never wins, just begins losing slower, is as tense as '80s action gets.

Raiders Of The Lost Ark

For the first and last time in history, Steven Spielberg was in trouble. Between "Jaws" and "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," he'd earned a reputation for running over schedule and budget. Studios didn't mind until "1941," a similarly extravagant production that only grossed a third of his earlier blockbusters. Even with a story and oversight from "Star Wars" creator George Lucas, Spielberg could barely get hired. His next project had to count.

"Raiders of the Lost Ark" cost about half of "1941" and came in 12 days ahead of schedule. It also happens to be the greatest adventure film ever made. In their nostalgic distillation of the pulpy '30s adventures that inspired them, Spielberg and company managed to usurp the very definition in pop culture; when anybody talks about "adventure serials" now, they really mean Indiana Jones.

The boulder. The truck. The swordsman. The flying wing. The action in "Raiders" is nothing short of iconic. Every set piece doubles as a self-contained silent film, just as effective when left to John Williams' orchestral lonesome. Harrison Ford's natural gift for frustration pays dividends with each punch. Lucas and Spielberg set out to make "something better than Bond." Against all odds, they did.

The Road Warrior

With "The Road Warrior," director and co-writer George Miller forged a legend. The nuked-out horizon. The leather-punk fashion. The wandering mute on a road to nothing and nobody. Sure, the component parts came from somewhere. But the view, damned and dirty, seems like it has always existed as-is. Even the original "Mad Max" looks like a smudged Xerox by contrast.

The plot is exactly one-word-long: survival. Max needs gas and dog food. The rest, humanity included, is a detour. In place of heroics, there are deals. In place of compassion, there's desperate trust. "You want to get out of here?" he asks the latest pocket of delusional civilization. "Talk to me." It might as well be a hug. Max's one smile is sarcastic, seen only when his luck runs out and the status quo settles down again.

Reducing "The Road Warrior" to its climactic chase is disingenuous only because Miller did that himself 34 years later with the superlative "Mad Max: Fury Road." Even in that considerable shadow, this film's vehicular carnage stands the tests of time and imitation -- nothing beats a marauder accidentally flipping end-over-end three times in mid-air. "Fury Road" is the superior smash-'em-up, no question, but atomic westerns don't get any better than "The Road Warrior."

Police Story

"Police Story" is the product of a man possessed. Jackie Chan was running out of time and patience. Both of his attempts to woo audiences in the United States, 1980's "The Big Brawl" and 1985's "The Protector," failed. His frustrations with American directors are best summarized with a single grievance, aired when the latest potential stunt was dumbed down for coverage: "No one's going to pay money to watch Jackie Chan taking a stroll." If Chan wanted a true showcase for his abilities, he'd have to build his own and throw himself through it repeatedly.

The story is a cops and robbers tale pitting the determined Sergeant Ka-Kui versus omnipotent crime lord Chu Tao. The plot is an excuse; Chan and co-writer Edward Tang reverse-engineered it from a list of props and playgrounds. By the director-star's estimation, the film cost a little less than $2 million American dollars, a quarter of the budget of that same year's "Police Academy II: Their First Assignment." Chan made up the difference in blood.

"Policy Story" opens with Ka-Kui leveling a shantytown in a compact car, and only gathers speed from there. Any given set piece, any given shot, would earn far lesser works a prime seat in the action movie pantheon. The sum total, furiously alive with a breath Chan never lets himself catch, approaches the sublime.

Die Hard

"Terrorist movies are usually mean, filled with all sorts of mean, nasty acts," admits director John McTiernan on the "Die Hard" DVD commentary. "I didn't say yes to this project until we figured out some ways to put, in essence, some joy in it." That fleet-footed contradiction produced not only one of the greatest action movies ever made, but the most influential -- how many films can claim an entire knock-off genre?

But there is no substitute for "Die Hard," not even its sequels. The original is among the finest Swiss watches ever crafted and blown to smithereens. The script, feverishly rewritten by Steven E. de Souza mid-shoot to accommodate Bruce Willis' "Moonlighting" schedule, should be studied in film school. The rhythm, co-conspired by McTiernan, cinematographer Jan de Bont, and editor Frank Urioste, changed the visual language of American action cinema. It also signaled the superman's twilight, substituting the reigning gym rats for ragdoll Bruce Willis.

John McClane is a '70s cop in an '80s plight. He wounds -- oh boy, does he wound -- and winces at every muzzle flare. Most importantly, he thinks. Not once does McClane get the upper hand in any physical sense. Instead, he starts on the back, bare foot and never quite recovers. His only advantage is that the wily villains, led by Alan Rickman in one of the all-time greatest acting debuts, assume that they're wilier than he is. What makes "Die Hard" work is that McClane would probably agree with them. But that's never stopped him before, and now he's got a machine gun. (Ho. Ho. Ho.)

Commando

"It's the granddaddy of action films as we know them today," says director Mark Lester, "and Arnold was the reason it got made." Any confusion over its inspiration is cleared up before the opening credits -- Mr. Universe walks out of the woods with an entire tree perched on one shoulder. He's not Rambo. He's not Conan. He's Paul Bunyan resurrected for the Reagan age, his axe traded in for a belt-fed M60 machine gun and his name rechristened by the Commodore 64 — John Matrix.

Its purity transcends all cultural barriers. "You don't need to read the subtitles to know it was a bad idea to kidnap Arnold Schwarzenegger's little girl," says screenwriter Steven E. de Souza. The kidnappers awaken a force as simple and inevitable as death itself. Mall security. Air traffic control. Physics. Nothing can stop John Matrix, an ontological truth only former squad mate Vernon Wells, an eleventh-hour replacement worth his weight in weirdo gold, understands. He will jump from planes that are taking off, roll down mountains in Chevy Blazers with their brakes cut, and gun down hundreds of foreign soldiers somehow stationed on an island off the California coast in order to get Alyssa Milano back.

And he does, all to the percussive beat of James Horner's steel drums. Not a second or shell casing is wasted. Any given line could be sold on a t-shirt. The obligatory pop song at the end describes Arnold's daughter as "a mountain that dreams are made of." To call "Commando" the greatest '80s action movie still sells it short -- this is the ultimate '80s action movie, a rocket-propelled time capsule that still blows up with the best of them.

Read this next: Butkus To Punchy: Ranking All 8 'Rocky' Movies From Worst To Best

The post The 16 best '80s action movies ranked appeared first on /Film.

0 Commentaires